On Tuesday, January 19 at 7:00 p.m. on NPT-Channel 8 and PBS stations nationwide, NOVA turns its scientific eye toward “The Riddles of the Sphinx.” For 45 centuries, the Great Sphinx, the biggest and oldest statue in a land of colossal ancient monuments, has lorded over Egypt’s Giza plateau. Its scale is staggering: the mighty head towers as tall as the White House, while its body is nearly the length of a football field. This strange half-human, half-lion image has inspired countless fantastic theories about its origins. How was it built, and who or what does it represent? Surprisingly, the scribes of the period when it was built — during Egypt’s Old Kingdom — passed over it in silence. Adding to the mystery, archeologists found that its creators abruptly discarded their tools and abandoned the structure when it was nearly complete. Searching for clues, NOVA’s expert team of archeologists, including Mark Lehner (director, Ancient Egypt Research Associates), carries out eye-opening experiments that reveal the techniques and incredible labor invested in the carving of this gigantic sculpture. The team also unearths new discoveries about the people who built the Sphinx and why they created such a haunting and stupendous image.

If you’ve never been to the Great Sphinx, it’s hard to truly grasp its magnificence. Most will never see it in person, and that’s why there are photographers, videographers, filmmakers and most notably, where this post is concerned, writers.

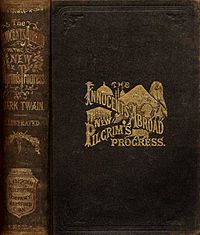

Because we’re still in Nashville’s Citywide Celebration of Mark Twain, which kicked off in September, I thought it best to go to America’s most famous novelist, essayist and humorist to describe the Sphinx. In The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrims’ Progress , Twain recounts his journey with religious pilgrims to Europe and the Holy Land aboard the The Quaker City steamship. It’s at times funny, sobering, reverent, irreverent, cruel, caring, tedious and tremendous. While now considered a minor work of Twain’s, it’s easily a major work of travel writing, and was one of his most popular during his lifetime.

Published in 1869, it came before many of the great novels he became famous for, but there are flashes of beauty, and boundless wit, that hint of what was to come.

Twain’s take on the Sphinx is one of those moments. It needs no further introduction, so I’ve pasted it here, thanks to the Complete Works of Mark Twain at MTWAIN.com

from Chapter LVIII

After years of waiting, it was before me at last. The great face was so sad, so earnest, so longing, so patient. There was a dignity not of earth in its mien, and in its countenance a benignity such as never any thing human wore. It was stone, but it seemed sentient. If ever image of stone thought, it was thinking. It was looking toward the verge of the landscape, yet looking at nothing — nothing but distance and vacancy.

It was looking over and beyond every thing of the present, and far into the past. It was gazing out over the ocean of Time — over lines of century-waves which, further and further receding, closed nearer and nearer together, and blended at last into one unbroken tide, away toward the horizon of remote antiquity. It was thinking of the wars of departed ages; of the empires it had seen created and destroyed; of the nations whose birth it had witnessed, whose progress it had watched, whose annihilation it had noted; of the joy and sorrow, the life and death, the grandeur and decay, of five thousand slow revolving years. It was the type of an attribute of man — of a faculty of his heart and brain. It was MEMORY — RETROSPECTION — wrought into visible, tangible form. All who know what pathos there is in memories of days that are accomplished and faces that have vanished — albeit only a trifling score of years gone by–will have some appreciation of the pathos that dwells in these grave eyes that look so steadfastly back upon the things they knew before History was born — before Tradition had being — things that were, and forms that moved, in a vague era which even Poetry and Romance scarce know of — and passed one by one away and left the stony dreamer solitary in the midst of a strange new age, and uncomprehended scenes.

The Sphynx is grand in its loneliness; it is imposing in its magnitude; it is impressive in the mystery that hangs over its story. And there is that in the overshadowing majesty of this eternal figure of stone, with its accusing memory of the deeds of all ages, which reveals to one something of what he shall feel when he shall stand at last in the awful presence of God.

There are some things which, for the credit of America, should be left unsaid, perhaps; but these very things happen sometimes to be the very things which, for the real benefit of Americans, ought to have prominent notice. While we stood looking, a wart, or an excrescence of some kind, appeared on the jaw of the Sphynx. We heard the familiar clink of a hammer, and understood the case at once. One of our well meaning reptiles — I mean relic-hunters — had crawled up there and was trying to break a “specimen” from the face of this the most majestic creation the hand of man has wrought. But the great image contemplated the dead ages as calmly as ever, unconscious of the small insect that was fretting at its jaw. Egyptian granite that has defied the storms and earthquakes of all time has nothing to fear from the tack-hammers of ignorant excursionists — highwaymen like this specimen. He failed in his enterprise. We sent a sheik to arrest him if he had the authority, or to warn him, if he had not, that by the laws of Egypt the crime he was attempting to commit was punishable with imprisonment or the bastinado. Then he desisted and went away.

The Sphynx: a hundred and twenty-five feet long, sixty feet high, and a hundred and two feet around the head, if I remember rightly — carved out of one solid block of stone harder than any iron. The block must have been as large as the Fifth Avenue Hotel before the usual waste (by the necessities of sculpture) of a fourth or a half of the original mass was begun. I only set down these figures and these remarks to suggest the prodigious labor the carving of it so elegantly, so symmetrically, so faultlessly, must have cost. This species of stone is so hard that figures cut in it remain sharp and unmarred after exposure to the weather for two or three thousand years. Now did it take a hundred years of patient toil to carve the Sphynx? It seems probable.

2 Comments

NOVA and Mark Twain on the Riddles of the Sphinx – News and Programming Updates From Nashville Public Television has a number of genuinely marvellous work on behalf of the owner of this site, perfectly outstanding subject material. Thanks ! Los Angeles Attorney !…

If some one needs to be updated with most recent technologies then he must be pay a visit this web page and be up to date all the time.