By Rob DeHart

Tennessee State Museum

In episode three of Mercy Street, Dr. Foster and Nurse Hastings are sent to treat a Union Army officer for a sexually transmitted disease. The episode touches upon the prevalence of prostitution in occupied cities and military camps during the Civil War. Nashville not only experienced this problem, but also took the extraordinary step of legalizing prostitution in an effort to control sexually transmitted diseases among the city’s prostitutes and Union Army soldiers.

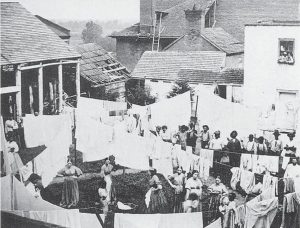

Prostitution existed in Nashville long before the Civil War. Poor single women and widows were especially vulnerable because 19th-century society provided few employment opportunities for women. In fact, newspapers often referred to prostitutes as “abandoned women,” suggesting that their condition resulted from not having husbands. In response, some elite women and men in Nashville set up charities to help poor single women stay out of prostitution. One of these charities was the House of Industry for Females established in 1837. The institution took orphaned girls and young women off the streets of Nashville and trained them in domestic skills.

Prostitution existed in Nashville long before the Civil War. Poor single women and widows were especially vulnerable because 19th-century society provided few employment opportunities for women. In fact, newspapers often referred to prostitutes as “abandoned women,” suggesting that their condition resulted from not having husbands. In response, some elite women and men in Nashville set up charities to help poor single women stay out of prostitution. One of these charities was the House of Industry for Females established in 1837. The institution took orphaned girls and young women off the streets of Nashville and trained them in domestic skills.

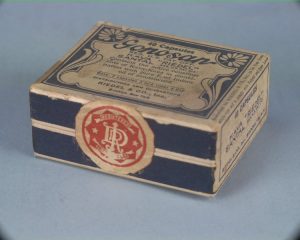

Prostitution flourished in Civil War Nashville for two reasons. First, the war disrupted working-class families sending men into the army or exile, leaving many women without a means of financial support. Second, the city experienced the influx of thousands of Union soldiers, many looking for ways to relieve the boredom of camp life. As a result by mid-1863, sexually transmitted diseases had reached epidemic proportions among soldiers. As seen in Mercy Street, medical treatment for these diseases was painful, not always effective, and could sideline a soldier for weeks.

To curb the epidemic, the Union Army came up with an extreme solution: It directed that all prostitutes in the city be rounded up and transported north. Estimates range from a few hundred to a thousand women being forced to leave the city via rail or steamboat. One documented transport was the steamer Idahoe, which tried to deliver a group of these women to the city of Louisville. After Louisville refused to accept the women, the steamer traveled further upriver to Cincinnati, but was again rejected. After a 28-day trip, the steamer returned the women to Nashville charging the army $1,000 for damages to the quarters of the vessel and more than $4,000 for food and medicine.

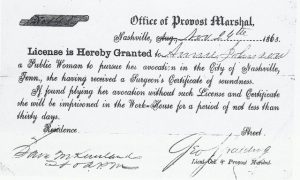

With the army’s plan to remove the prostitutes a failure, it decided that the best way to control sexually transmitted diseases in Nashville was to create a licensing system for the women, essentially legalizing prostitution in the city. The army announced that all prostitutes were to report for a medical examination or risk serving 30 days in jail. If found disease-free, the women were required to pay $1 license fees and would be permitted to practice their profession as long as they returned every 14 days for a follow-up examination. If a woman was found to have a sexually transmitted disease, she would receive proper treatment in a hospital set up specifically for prostitutes.

According to army reports, 393 prostitutes were licensed following the implementation of this plan. By January 1865, 207 women and 2,330 men were treated for sexually transmitted diseases in Nashville. One of the hospitals for the prostitutes was located on 2nd Avenue, probably north of Gay Street. The hospital for the men was located in the former Hynes School building (built in 1857) on the corner of Jo Johnston Street and 5th Avenue. Neither building exists today.

The army terminated the plan in Nashville when the war ended. Today, a few counties in the United States have legalized prostitution and it is noteworthy that these prostitution licensing systems are not too different from what was instituted in Nashville in 1863.

Mercy Street airs 7 p.m. Sundays on NPT.

Rob DeHart received his M.A. in public history from Middle Tennessee State University, is a peer reviewer for the American Alliance of Museums and is currently developing content for the new Tennessee State Museum opening in 2018.

2 Comments

Another in the LONG line of great programming by NPT! As a native of Nashville, I thoroughly enjoyed the additional information on the Civil War. Thanks.

We’re glad you’re enjoying Mercy Street and Rob DeHart’s blog posts!