By Allison Inman

When I tell friends I’m working on a documentary about Elia Kazan’s 1960 film Wild River, I don’t often hear that “ahh” of recognition. Despite being revered by modern critics, it’s never been released on DVD in the U.S., so it lurks in the shadow of Kazan giants like East of Eden and On the Waterfront. I expect that to change soon, however, as Martin Scorsese’s new documentary A Letter to Elia airs on NPT and PBS stations nationwide (October 4), and Wild River finally arrives on DVD in a Kazan box set, 50 years after it hit theaters.

Wild River is the story of a Tennessee Valley Authority bureaucrat (Montgomery Clift) coaxing a stubborn family matriarch (Jo Van Fleet) off her land to make way for “progress” – the TVA’s systematic flooding of the region that would bring power and jobs during the Great Depression. It co-stars Lee Remick in the role of Van Fleet’s widowed granddaughter Carol, who falls in love with the TVA man. It also happens to be the first major motion picture shot in its entirety in Tennessee.

Wild River is the story of a Tennessee Valley Authority bureaucrat (Montgomery Clift) coaxing a stubborn family matriarch (Jo Van Fleet) off her land to make way for “progress” – the TVA’s systematic flooding of the region that would bring power and jobs during the Great Depression. It co-stars Lee Remick in the role of Van Fleet’s widowed granddaughter Carol, who falls in love with the TVA man. It also happens to be the first major motion picture shot in its entirety in Tennessee.

Kazan began conceptualizing Wild River after a stint with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (he assistant directed a 1937 labor movement propaganda film called People of the Cumberland) and subsequent interest in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, specifically the TVA.

Scouting locations for Wild River, Kazan flew 650 miles from Paducah, Kentucky, to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, looking for the setting he saw in his mind. He found it in Bradley County, Tennessee, along the banks of the Hiwassee River.

The film’s most charged setting – a bend of river with history on one side, “progress” on the other, and a pole-operated ferry for drifting back and forth – is a spot on the Hiwassee River called Coon Denton, a few miles from Charleston. Overlooking it is a white cottage locals now call the Lee Remick House. The rest of the film was shot in tiny downtown Charleston, most of which is gone now; on sets inside the National Guard Armory in nearby Cleveland; and on the banks of Lake Chickamauga in Hamilton County, now in view of TVA’s Sequoyah Nuclear Plant towers.

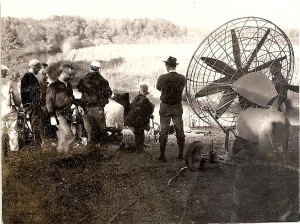

Besides the setting, Kazan realized what the local people could bring to his production. He offered speaking parts to more than 40 locals and hired over 100 more as extras, stand-ins and crew. Kazan loved to study people, jab at them, discover their idiosyncrasies. His affection for Bradley County residents was evident – he corresponded for years with Carolyn Harris and her daughter, Judy, who played Lee Remick’s little girl in the film. They liked him too, and if anyone in this ultra-conservative region knew a thing about his Communist views, they didn’t seem to care.

I was hired to direct the documentary by Life Care Centers of America’s Media Center and the Cleveland/Bradley County Chamber of Commerce. We are recording an important event in the town’s history, but I think we’re getting much more. Our film is a humble, low-budget recollection of Wild River stories from the hometown point of view. We tell about the movie by following the citizens of Bradley County – notably David Swafford, a second-shift welder who’s writing a book about Wild River – as they prepare for their Wild River 50th Anniversary Celebration, which happened in June of this year.

The stories, if you’re into Southern characters, are good. They’re also a bit cloudy – after all, most of the key figures have passed on. But that’s merely part of the fun. We follow David in his earnest obsession to find film artifacts and the truth behind local legends. There’s debate, for example, about who gave Montgomery Clift, who was struggling with pills and alcohol, his first sip of moonshine. Nine people claim that they were the owner of the blue tick hound dog who played Ol’ Blue in the film. White folks remember the premiere of the movie at Star-Vue Drive-in, but black cast members don’t remember being invited – or for that matter being welcome at the Star-Vue at all.

Film aficionados, East Tennessee residents of a certain age, and TVA retirees will tell you that Wild River is one of Elia Kazan’s most impressive and underrated movies. Some even call it his masterpiece.

I’m glad the greater public will soon get a chance to see for themselves.

Allison Inman is an independent filmmaker and the ITVS Community Cinema coordinator for Nashville. Her documentary on the making of Wild River should be available next year. A Letter to Elia airs on NPT and PBS stations nationwide on Monday, October 4 at 8:00 p.m. Central.

4 Comments

Kazan’s “Communist views”? Umm, I would strongly suggest you do some research on Kazan before you make your film. While he had those views in the 1930s, he was an anti-Stalinist, and most famous, or infamous, for naming alleged Communists before HUAC in the 1950s. Certainly by this time, he had anything but Communist views.

Umm, thank you, Lotte Lenya. Yes, I’m familiar with Kazan’s story, and I understand your point. I should have said “former Communist views” or “Kazan’s past with the American Communist Party” to clarify.

The best book so far to learn card games is Harrington. I’ve noticed, that lot’s of people improved their skills just by reading it – so I strongly recommend to buy this book and read it. Not only one time, but use it during game. Really improves!

lower back pain, physical theraphy…

[…]When Elia Kazan Came to East Tennessee – News and Programming Updates From Nashville Public Television[…]…