If you caught the Frist Center for the Arts exhibit “Extra-Ordinary: The Everyday Object in American Art” in late 2006-early 2007, you might remember a piece by Felix Gonzales-Torres. NPT Media Update Arts Correspondent Daniel Tidwell comments on the announcement that Gonzalez-Torres will represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale. Look for Tidwell’s arts column to appear here at least every second Tuesday of the month.

Years ago at the Museum of Modern Art on a bitter cold winter afternoon, I along with my five year-old daughter, came across one of Felix Gonzalez Torres’ signature stacks of printed paper, installed as part of the Museum’s permanent collection. The image on this particular piece was of the ten most wanted criminals (or something along those lines). I remember that the images were fairly disturbing. As we looked at the piece and a guard hovered in the corner of the room, viewers milled about and every once in a while someone would pick up one of the prints, roll it up and walk off with it. This astounded my daughter who had been taught for years to never touch anything in a museum. I explained to her that the artist meant for these to be taken and that museum workers would print up more and replace them. I encouraged her to go and take one from the stack. She was too timid, so I walked up to take one and I recall that in that instant ― knowing full well that this was what the artist intended ― I was worried that I was about to get into big trouble for defacing or attempting to steal a work of art. I took the print and rolled it up as others before without incident and we continued to make our way through the museum

I recalled this museum visit when I read that Gonzalez-Torres, who died in 1996, had been selected to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale. The brilliance of Gonzalez-Torres’ work is found in its visual simplicity, while its conceptual complexity calls into question the nature of a work of art, how a work of art can be exhibited, the curator’s role in defining a work of art and the power of the gallery and museum in defining a work’s value. Consequently, it calls into question the artist’s role in defining originality on his own terms. More subtly, the art questions and critiques our country’s power structure, the marginalization of the “other” and the AIDS crisis.

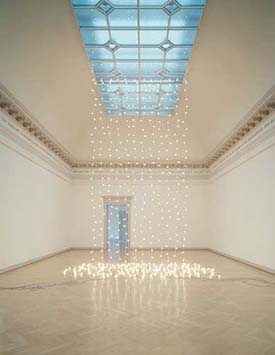

Recently one of Gonzalez-Torres’ light strands was on view at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts as part of the “Extra-Ordinary: The Everyday Object in American Art” exhibition from the Whitney Museum. The piece consists of a simple strand of clear light bulbs that can be displayed in any manner that a curator chooses. At the Frist this piece had been hung on a wall near the end of the exhibition, while at the Biennale a similar piece has been hung from the ceiling of a circular rotunda where it takes on much more of a sculptural quality than the installation here in Nashville. The piece is evocative of many literal interpretations—yet its challenging nature lies in its ability to test viewers’ traditional notions of what constitutes a work of art and how a work should be displayed. Shortly after the show at the Frist opened I had several heated discussions with a co-worker who felt that the piece’s formal and political content was simply too inscrutable ― impossible for the general public to read — and therefore something of a sham perpetrated by the artist for a very small audience of art world insiders. At some level these points were valid in that, yes, a viewer needs to know something about the artist and his intentions to make a correct interpretation of this piece and to see the broader conceptual implications. However, I argued that this is the case with all good art — it requires the viewer to at least meet the artist half-way. Furthermore, something that is easily understandable at first glance probably isn’t great art and probably isn’t deserving of the viewers’ attention.

I’m not sure if this particular argument ever came to any resolution. I think the discussion may have ended after I referred to a particular point made by my coworker as a literalistic and 19th century interpretation of contemporary art. The work certainly proved its essential power to provoke the viewer and raise important questions about the nature of contemporary art.

In so many ways, Gonzalez-Torres seems like the perfect selection for the U.S. Pavilion at Venice this year. As a gay Cuban émigré, Gonzalez-Torres’ personal history and his challenging and tough work reflects the diversity of our country. Most importantly, his work continues to challenge its viewers and incite debate and discussions on what art is, what an artist is and ultimately, how art functions in a socio-political context.