This week Your Daily Arts Break has taken a look at artists including Sam Durant, Edgar Arceneaux and Renee Green that are concerned with redefining history by referencing shifts in the perceptions of social history that occurred in a definitive moment at the dawn of the 70’s through the work of land artists like Robert Smithson. The image from Mark Tansey of Native Americans taking in the view of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty was thrown in for the sheer irony of the image and its value as a visual one liner.

Through heroic works such as Spiral Jetty and by contrast through the abject Partially Buried Woodshed, Smithson ushered in a new paradigm of sculpture as Rosalind Krauss described in her seminal 1974 essay Sculpture in the Expanded Field. In this essay Krauss seeks to make sense of a new development in sculpture–minimalism, specifically land based art including the work of Smithson, Robert Morris, Richard Serra, Walter DeMaria and Robert Irwin. Krauss describes prior efforts to understand the work in historical terms as efforts to make “the new”…”comfortable” by making it familiar. In Krauss’ words, “Historicism works on the new and different to diminish newness and mitigate difference. It makes a place for change in our experience by evoking the model of evolution…no sooner had minimal sculpture appeared on the horizon of the aesthetic experience of the 1960’s, than criticism began to construct a paternity for this work, a set of Constructivist fathers who could legitimize and thereby authenticate the strangeness of these objects. Never mind that the content of the one had nothing to do with, was in fact the opposite of, the content of the other. The rage to historicize simply swept these differences aside. “

Krauss goes on to say that “As the 1960’s began to lengthen into the 1970s and ‘sculpture’ began to be piles of thread waste on the floor, or sawed redwood timbers rolled into the gallery, or tons of earth excavated from the desert,… the word sculpture became harder to pronounce, but not really that much harder. The historian/critic simply performed a more extended slight-of-hand and began to construct his genealogies out of the data of millennia…Stonehenge, the Nazca Lines, the Toltec ball courts–anything could be hauled into court to bear witness to this works’ connection to history and … legitimize its status as sculpture. Of course Stonehenge and the Toltec ball courts were just exactly NOT sculpture.”

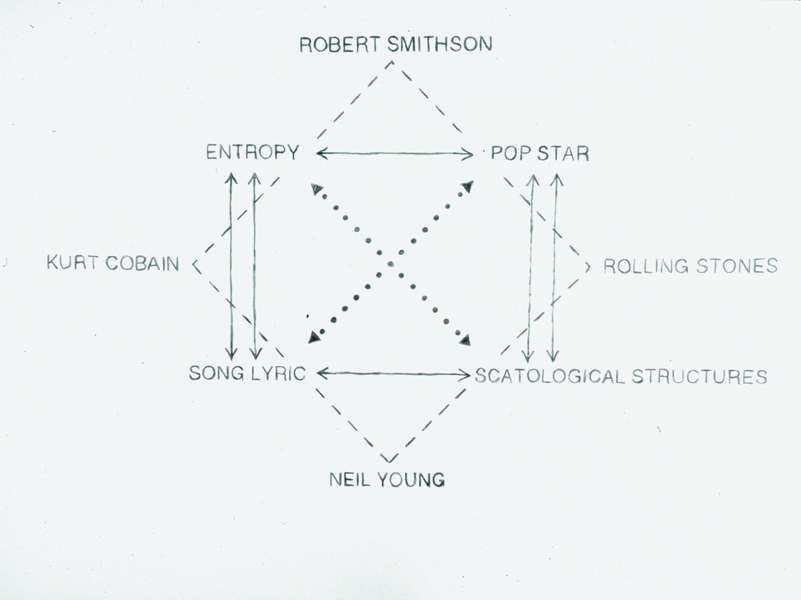

In her typically brilliant fashion, Krauss then posits a structuralist model to define these new forms of, what she refers to as, anti-sculpture which exist outside of historical terms. In Krauss’ model, sculpture in the expanded field includes marked sites, axiomatic structures, site-construction and traditional sculpture. This field characterizes the “domain of postmodernism” where the “purity” of modernism is cast aside and an artist is free to utilize any medium necessary. “Within the situation of postmodernism, practice is not defined in relation to a given medium…but rather in relation to the logical operations on a set of cultural terms, for which any medium–photography, books, lines on walls, mirrors, or sculpture itself–might be used.” Krauss concludes her essay by saying that “this is obviously a different approach to thinking about the history of form from that of the historicist criticism’s constructions of elaborate genealogical trees. It presupposes the acceptance of definitive rupture and the possibility of looking at historical process from the point of view of logical structure.”

Rereading her essay brings to mind a trend that is prevalent in art reportage, particularly on a regional level. It’s a trend that can be referred to as the “look alike” method of writing about or analyzing art. A typical “look alike” essay does exactly what Krauss criticizes. It draws on simplistic, historical references and look-alike relationships to try to explain the meaning of a work of art, relying on comparisons of things that have absolutely nothing to do with each other on a formal or structural level. A good example would be a recent review of the Thornton Dial exhibition at The Frist Center which links a Dial work, Memory of the Ladies That Gave Us the Good Life, to Robert Rauschenberg’s Bed. Dial’s work does look like certain Rauschenberg pieces but, on a formal or structural level is really unrelated. This mode of writing does demonstrate knowledge of art history, as opposed to the other manner of writing about art, also widespread, which simply is comprised of a verbal description of the works in an exhibit with no reference to anything other than a theme, taken from the exhibition press release. This method of art criticism is best described by Truman Capote’s famous description of Jack Kerouac’s work: “That’s not writing, it’s typing”.

Nashville has a growing and vibrant visual arts scene and since its founding The Frist Center for the Visual Arts has been a game changer–providing Nashville with access to art which simply wasn’t available before. The most recent example of the Frist taking the lead in developing new and innovative exhibitions is Fairy Tales, Monsters and the Genetic Imagination organized by Mark Scala. The show was a thoughtful and original look at fertile artistic fields being explored by many contemporary artists. In September The Frist will open what will prove to be their most important exhibition to date, the first retrospective of Carrie Mae Weems organized by Frist Center curator Kathryn Delmez.

It’s an opportune time for the Frist to open this show. The importance of the show has already been recognized by references in The New York Times and Time magazine and major articles in the art press will be forthcoming. When the show opens on September 21 the eyes of the art world will be on Nashville. Nashville’s community of creatives and artisans do a lot of things very well, earning deserved national recognition. One hopes that some of that nationally recognized creativity will filter down to those that write about or review art in Nashville and provide the eyes that will be on the city with a bit more insight into the Weems show than –“Wow, Carrie Mae Weems’ work is really like Cindy Sherman because she, like, photographs herself too.”